“Blood Poisoning” – New Research Sheds Light On Ancient Disease

Hippocrates, the ancient Greek physician and father of Western medicine, knew and wrote about the disease that he called “blood poisoning.” Today, we call it sepsis (from the Greek term for “to rot”), and the disease causes one million deaths in U.S. each year and probably tens of millions worldwide.

Because blood is pervasive in the human body, an infection of the blood, which is what happens with sepsis, can affect multiple organs simultaneously and make it extremely challenging to treat. Now, however, scientists have identified a gene that could potentially open the door for the development of new treatments of the lethal disease.

Researchers from The Australian National University and the Garvan Institute of Medical Research worked with Genentech, a leading United States biotechnology company, to identify a gene that triggers the inflammatory condition that can lead to the full-body infection sepsis.

“Isolating the gene so quickly was a triumph for the team,” said Professor Simon Foote, Director of The John Curtin School of Medical Research at ANU.

What Is Sepsis?

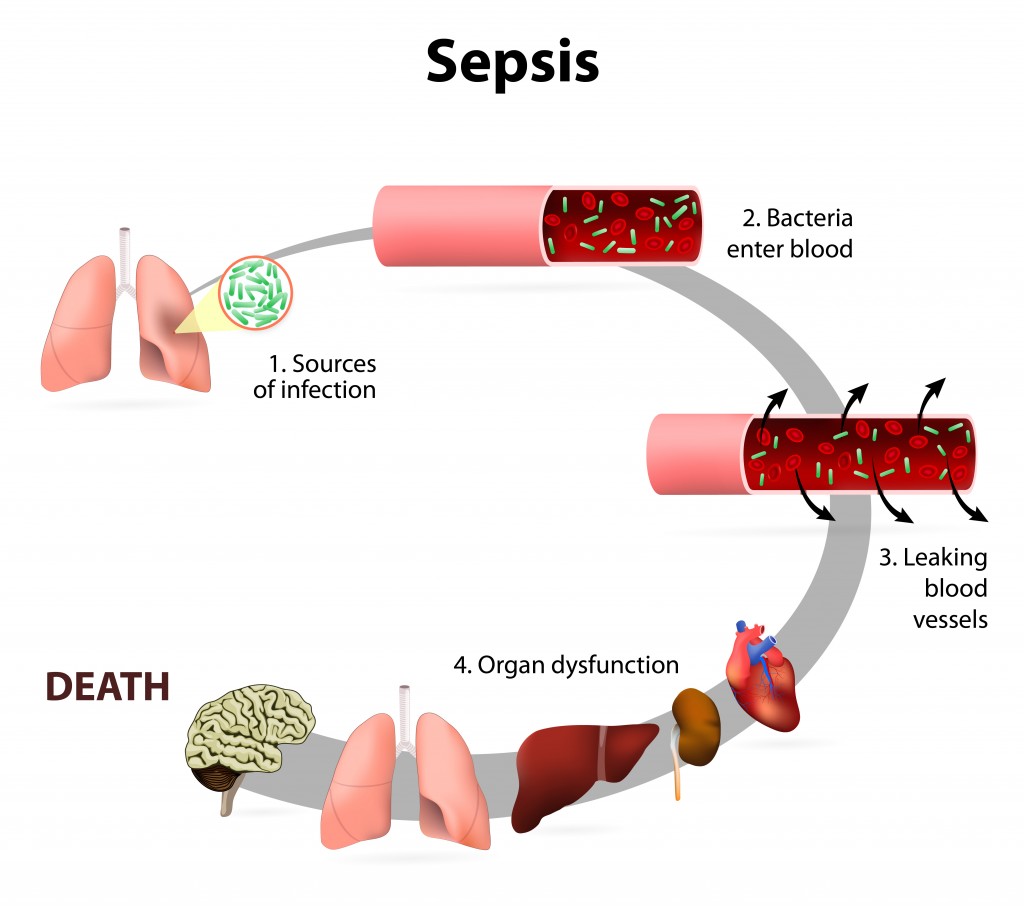

Sepsis is a severe whole-body infection. It occurs as a complication to an existing infection, and in that sense, represents a failure of the body’s immunological defenses to fight the initial infection. If not treated quickly it can lead to a condition called septic shock characterized by extremely low blood pressure, and multiple organ failure, with death rates as high as 50 per cent.

The infection is most commonly caused by bacteria, but also can be by fungi, viruses or parasites. Common locations for the primary infection include lungs (about 60% of the time), brain, urinary tract, skin and abdominal organs.

Currently, sepsis is treated with intravenous fluids and antibiotics, often done in an intensive care unit. If fluid replacement is not enough to maintain blood pressure, medications that raise blood pressure can be used. Mechanical ventilation and dialysis may be needed to support the function of the lungs and kidneys.

The key to treating sepsis is quickly identifying the disease. Patients with sepsis often arrive in ER classified as “code blue,” meaning pausing for a complete evaluation can prove fatal.

But what if sepsis could be stopped before it becomes life threatening? That was the focus of the current research to identify a gene linked to sepsis.

Preventing Blood Cells From Self-Destructing

Researchers were aware that sepsis occurs when molecules known as lipopolysaccharides (LPS) on the surface of some bacteria infiltrate cells, triggering an immune response that causes the cells to self-destruct. But exactly how the self-destruct button was pressed remained a mystery.

The team found the protein Gasdermin-D plays a critical role in the pathway to sepsis.

Scientists at Genentech showed that Gasdermin-D usually exists in cells in an inactive form. When the LPS molecules enter the cells they trigger an enzyme called caspase-11, a kind of chemical hatchet used to lop the protective chemical cap off Gasdermin-D, which in turn leads the cells to self-destruct.

How The Gene Was Isolated

The team at the Australian Phenomics Facility then screened thousands of genes with a large-scale forward genetics discovery platform and in a little over a year had isolated the gene that produces Gasdermin-D.

Nobuhiko Kayagaki, PhD, Senior Scientist from Genentech, said the work will help researchers understand and treat other diseases as well as sepsis. “The identification of Gasdermin-D can give us a better understanding not only of lethal sepsis, but also of multiple other inflammatory diseases,” he said.

Professor Chris Goodnow, from ANU and Garvan Institute of Medical Research was a co-author on the research paper, which was published in Nature. “This finding is a key that could potentially unlock our ability to shutdown this killer disease before it gets to a life-threatening stage,” Professor Goodnow said.

Sources:

Science Daily, “New Gene To Fight Sepsis,” Oct. 15, 2015, http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2015/10/151022103533.htm.

Wikipedia, “Sepsis,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sepsis.